Waves in plasmas

Title: Introduction to Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion

Authors: Francis F. Chen

Zotero link: Francis Chen - Introduction to Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion-Springer 2015 Compressed 2.pdf

Green

A criterion for an ionized gas to be a plasma is that it be dense enough that λD is much smaller than L.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 23)

A criterion for an ionized gas to be a plasma is that it be dense enough that λD is much smaller than L.

^highlight-p23x53y241

Questions

Debye shielding can be foiled if electrons are so fast that they do not collide with one another enough to maintain a thermal distribution. We shall see later that electron collisions are infrequent if the electrons are very hot. In that case, some electrons, attracted by the positive charge of the ion, come in at an angle so fast that they orbit the ion like a satellite around a planet. How this works will be clear in the discussion of Langmuir probes in a later chapter. Some like to call this effect antishielding.

[!quote]+ Note (Page 75)

Langmuir discovered that the electron distribution function was far more nearly Maxwellian than could be accounted for by the collision rate. This phenomenon, called Langmuir’s paradox, has been attributed at times to high-frequency oscillations. There has been no satisfactory resolution of the paradox,

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 111)

Because of the symmetry of Eq. (4.60), the case ωc > ωp is the same as the case ωp > ωc with the subscripts interchanged. For large kz, the wave travels parallel to B0. One wave is the plasma oscillation at ω ! ωp; the other wave, at ω ! ωc, is a spurious root at kz ! 1. For small kz, we have the situation of k ⊥ B0 discussed in this section. The lower branch vanishes, while the upper branch approaches the hybrid oscillation at ω ! ωh. These curves were first calculated by Trivelpiece and Gould, who also verified them experimentally (Fig. 4.22). The Trivelpiece–Gould experiment was done in a cylindrical plasma column; it can be shown that varying kz in this case is equivalent to propagating plane waves at various angles to B0 #Question

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 117)

This is called the lower hybrid frequency. These oscillations can be observed only if θ is very close to π/2. #Question

- How do we excite these waves?

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 129)

As a wave of given ω approaches the resonance point, both its phase velocity and its group velocity approach zero, and the wave energy is converted into upper hybrid oscillations. The extraordinary wave is partly electromagnetic and partly electrostatic; it can easily be shown (Problem 4.14) that at resonance this wave loses its electromagnetic character and becomes an electrostatic oscillation.

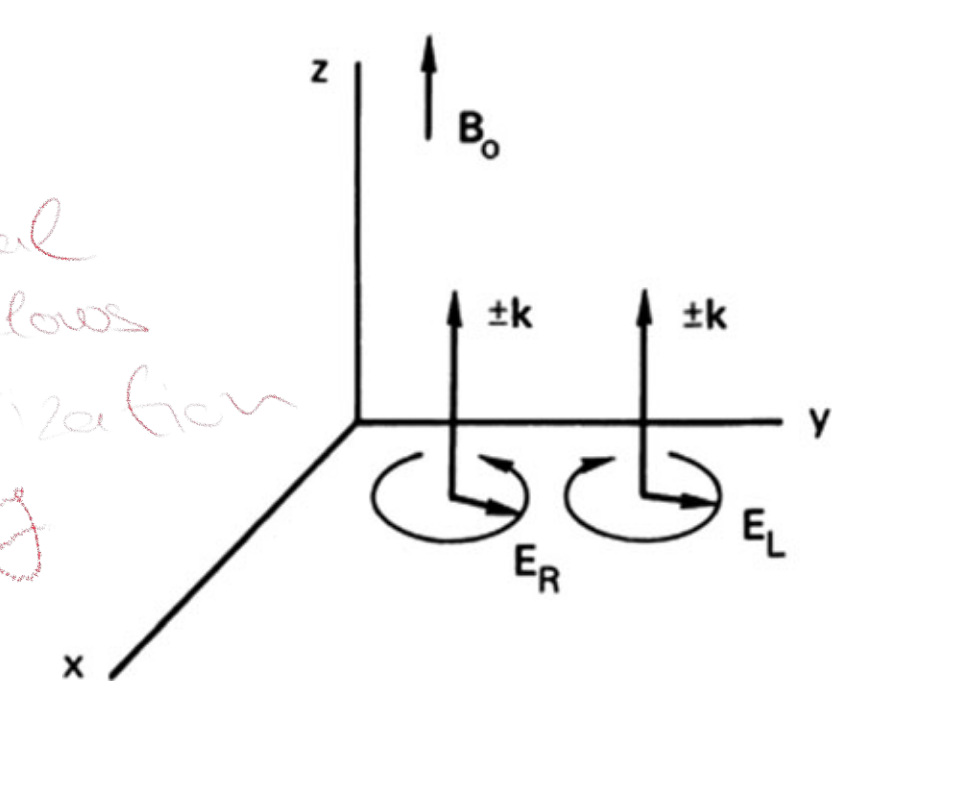

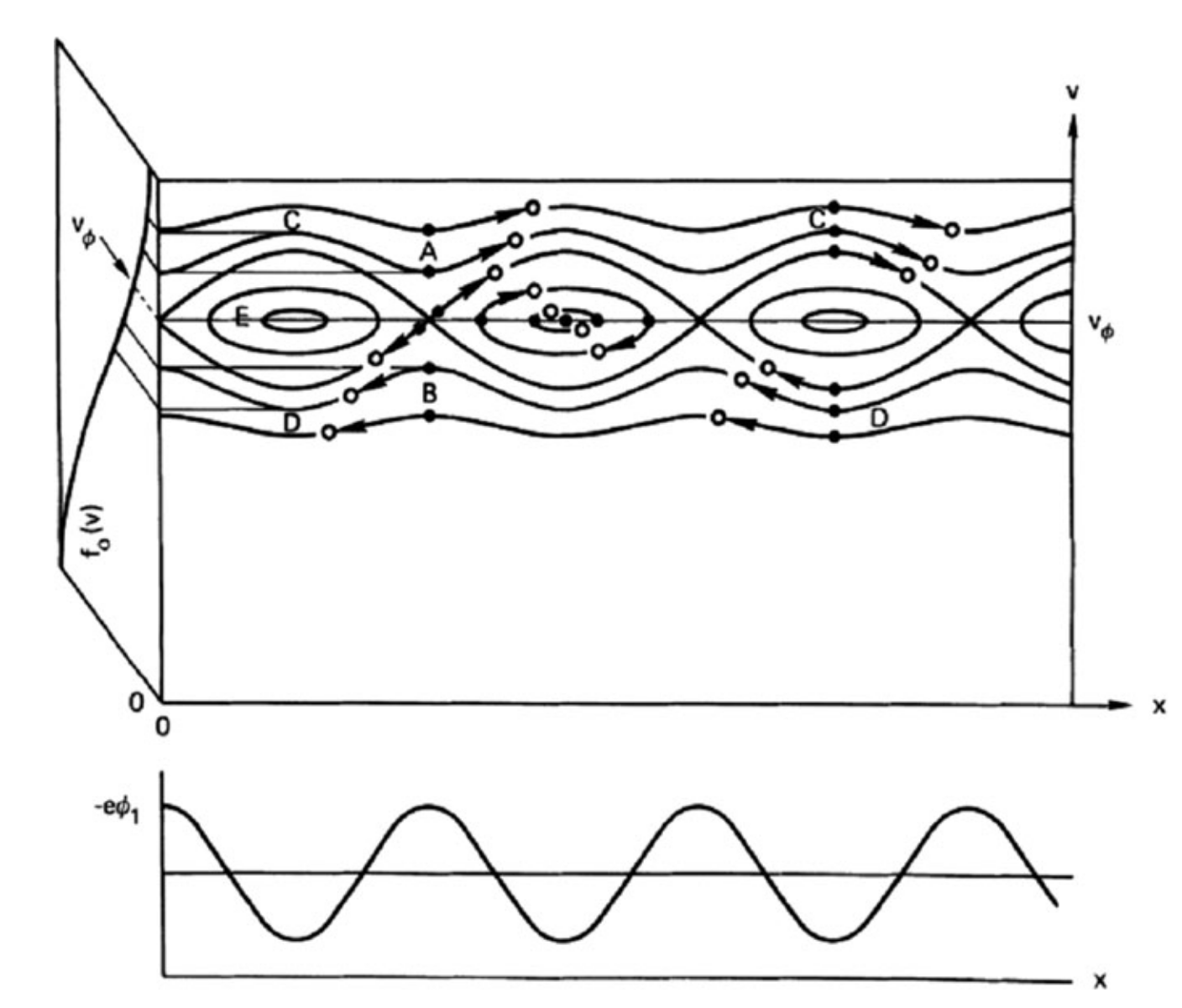

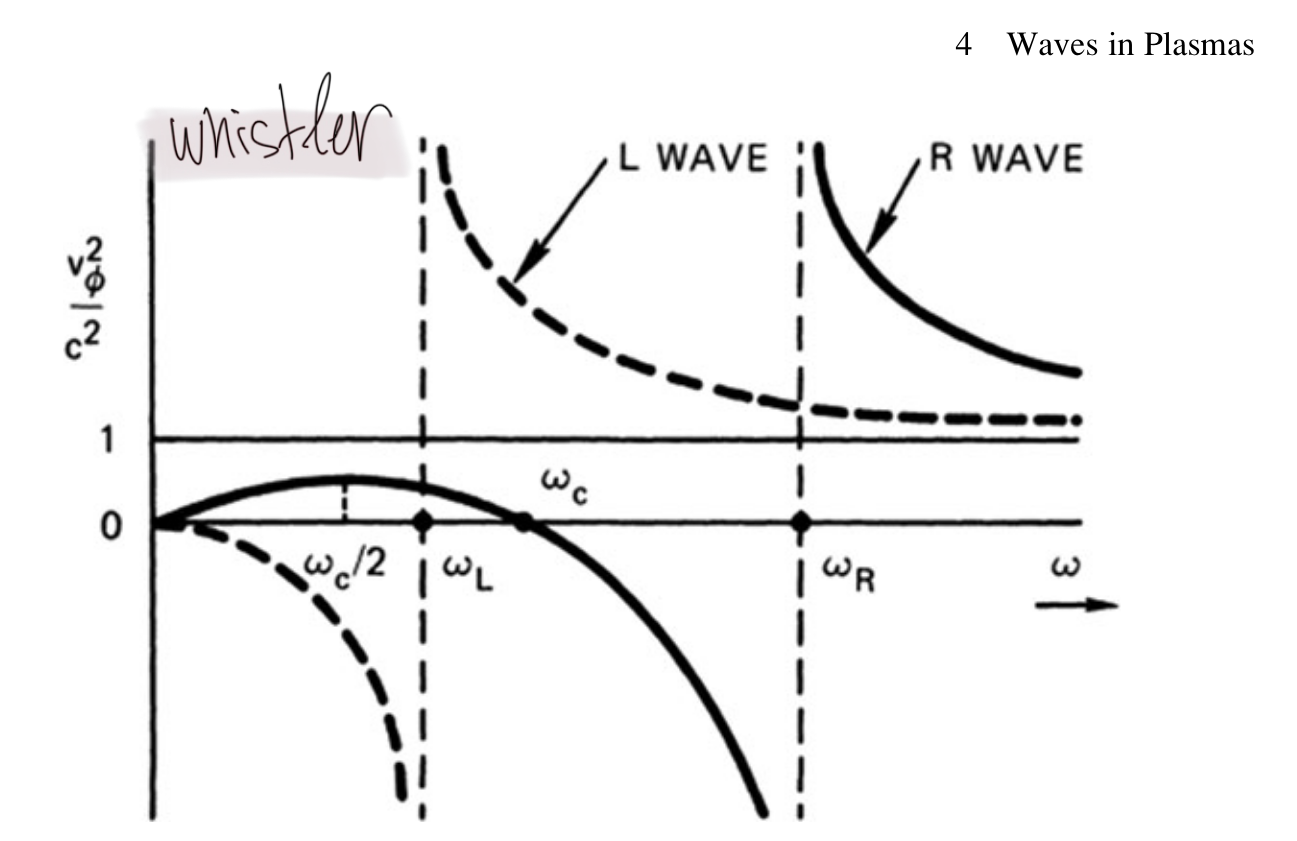

[!quote]+ Image (Page 133)

- What is the physical mechanism that allows the R wave rotation?

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 134)

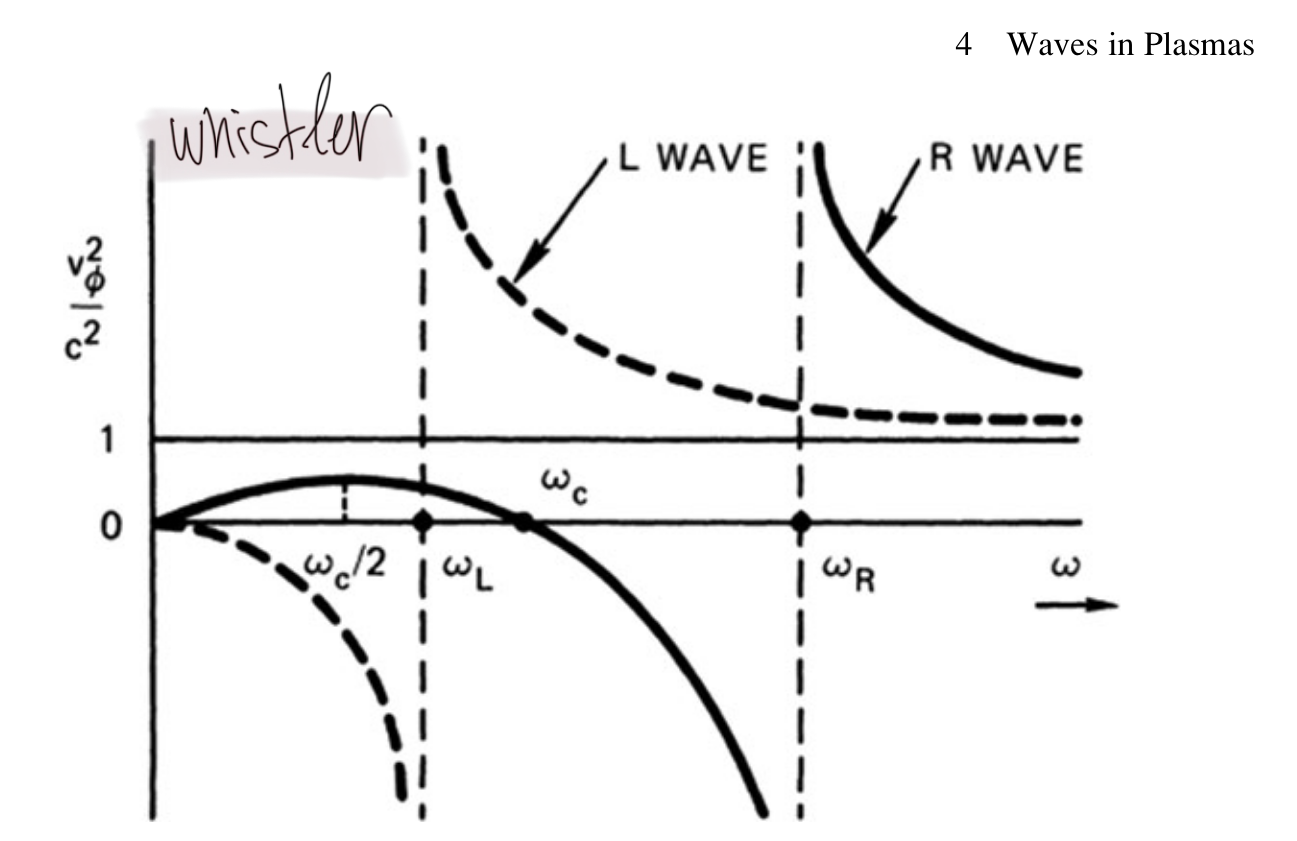

The L wave has a stop band at low frequencies; it behaves like the O wave except that the cutoff occurs at ωL instead of ωp. The R wave has a stop band between ωR and ωc, but there is a second band of propagation, with vφ < c, below ωc. #Question

- What is the physical cause of the cutoff?

[!quote]+ Image (Page 134)

- Understand whistler dispersion

[!quote]+ Note (Page 137)

In interstellar space, the path lengths are so long that Faraday rotation is important even at very low densities. This effect has been used to explain the polarization of microwave radiation generated by maser action in clouds of OH or H2O molecules during the formation of new stars. #Question

- How do we calculate the distance since we dont know the initial polarization? Can chaotic light get polarized and how?

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 146)

This is the dispersion relation for the magnetosonic wave propagating perpendicular to B0. It is an acoustic wave in which the compressions and rarefactions are produced not by motions along E, but by E * B drifts across E. In the limit B0 ! 0, vA ! 0, the magnetosonic wave turns into an ordinary ion acoustic wave. #Look-into

[!quote]+ Note (Page 170)

The steplength in the random walk is no longer λm, as in magnetic-field-free diffusion, but has instead the magnitude of the Larmor radius rL. #Question

- Where did we prove that the mean path is r_L?

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 242)

This is just the finite-temperature analogy of the two-stream instability. When there are two cold (KT ! 0) electron streams in motion, f0(v) consists of two δ-functions. This is clearly unstable because ∂f0/∂v is infinite; and, indeed, we found the instability from fluid theory. When the streams have finite temperature, kinetic theory tells us that the relative densities and temperatures of the two streams must be such as to have a region of positive ∂f0/ ∂v between them; more precisely, the total distribution function must have a minimum for instability. #Question

[!quote]+ Note (Page 243)

There are actually two kinds of Landau damping: linear Landau damping, and nonlinear Landau damping. Both kinds are independent of dissipative collisional mechanisms. #Question

- Since we derived it using linear theory, how can trapping not exist when there is energy transfer?

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 247)

84). It is intuitivelyclear that (1)hΔWkiis negative, since the block spends more time at the peaks than atthe valleys, and (2) the block does not gain or lose energy on the average, once theoscillation is started.

[!quote]+ Note (Page 248)

hiThese particles can absorbenergy from the wave and are properly called the “resonant” particles. As time goes on, the number of resonant electrons decreases, since an increasing number willhave shifted more than 1 2λ from their original positions. The damping rate, however,can stay constant, since the amplitude is now smaller, and it takes fewer electrons to maintain a constant damping rate. #Question

[!quote]+ Note (Page 249)

After a long time, the electrons are so smeared out in phase that the initial distribution is forgotten, and there is no further average energy gain, as we found in the previous section. In this picture, both the electrons with v > vφ and those with v < vφ when averaged over a wavelength, gain energy at the expense of the wave. #Question

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 23)

Debye shielding can be foiled if electrons are so fast that they do not collide with one another enough to maintain a thermal distribution. We shall see later that electron collisions are infrequent if the electrons are very hot. In that case, some electrons, attracted by the positive charge of the ion, come in at an angle so fast that they orbit the ion like a satellite around a planet. How this works will be clear in the discussion of Langmuir probes in a later chapter. Some like to call this effect antishielding.

^highlight-p23x53y62

Orange 🍊

Since T and Eav are so closely related, it is customary in plasma physics to give temperatures in units of energy.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 19)

It often happens that the ions and the electrons have separate Maxwellian distributions with different temperatures Ti and Te.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 19)

When there is a magnetic field B, even a single species, say ions, can have two temperatures. This is because the forces acting on an ion along B are different from those acting perpendicular to B (due to the Lorentz force). The components of velocity perpendicular to B and parallel to B may then belong to different Maxwellian distributions with temperatures T⊥ and T||.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 21)

On the other hand, if the temperature is finite, those particles that are at the edge of the cloud, where the electric field is weak, have enough thermal energy to escape from the electrostatic potential well. The “edge” of the cloud then occurs at the radius where the potential energy is approximately equal to the thermal energy KT of the particles, and the shielding is not complete. Potentials of the order of KT/e can leak into the plasma and cause finite electric fields to exist there.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 23)

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 23)

it is the electron temperature which is used in the definition of λD

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 23)

If the dimensions L of a system are much larger than λD, then whenever local concentrations of charge arise or external potentials are introduced into the system, these are shielded out in a distance short compared with L, leaving the bulk of the plasma free of large electric potentials or fields.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 23)

The plasma is “quasineutral”; that is, neutral enough so that one can take ni ’ ne ’ n, where n is a common density called the plasma density, but not so neutral that all the interesting electromagnetic forces vanish.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 24)

we can compute the number ND of particles in a “Debye sphere”:

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 24)

collective behavior

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 24)

If ω is the frequency of typical plasma oscillations and τ is the mean time between collisions with neutral atoms, we require ωτ > 1 for the gas to behave like a plasma rather than a neutral gas.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 32)

Plasmas behave sometimes like fluids, and sometimes like a collection of individual particles. The first step in learning how to deal with this schizophrenic personality is to understand how single particles behave in electric and magnetic fields.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 19)

Since T and Eav are so closely related, it is customary in plasma physics to give temperatures in units of energy. T

^highlight-p19x53y350

It often happens that the ions and the electrons have separate Maxwellian distributions with different temperatures Ti and Te.

^highlight-p19x53y184

When there is a magnetic field B, even a single species, say ions, can have two temperatures. This is because the forces acting on an ion along B are different from those acting perpendicular to B (due to the Lorentz force). The components of velocity perpendicular to B and parallel to B may then belong to different Maxwellian distributions with temperatures T⊥ and T||.

^highlight-p19x53y88

On the other hand, if the temperature is finite, those particles that are at the edge of the cloud, where the electric field is weak, have enough thermal energy to escape from the electrostatic potential well. The “edge” of the cloud then occurs at the radius where the potential energy is approximately equal to the thermal energy KT of the particles, and the shielding is not complete. Potentials of the order of KT/e can leak into the plasma and cause finite electric fields to exist there.

^highlight-p21x53y130

Note that as the density is increased, λD decreases, as one would expect, since each layer of plasma contains more electrons. Furthermore, λD increases with increasing KTe. Without thermal agitation, the charge cloud would collapse to an infinitely thin layer.

^highlight-p23x53y489

it is the electron temperature which is used in the definition of λD

^highlight-p23x53y476

If the dimensions L of a system are much larger than λD, then whenever local concentrations of charge arise or external potentials are introduced into the system, these are shielded out in a distance short compared with L, leaving the bulk of the plasma free of large electric potentials or fields.

^highlight-p23x53y325

The plasma is “quasineutral”; that is, neutral enough so that one can take ni ’ ne ’ n, where n is a ’ ’ common density called the plasma density, but not so neutral that all the interesting electromagnetic forces vanish.

^highlight-p23x53y265

we can compute the number ND of particles in a “Debye sphere”:

^highlight-p24x122y528

collective behavior”

^highlight-p24x150y480

If ω is the frequency of typical plasma oscillations and τ is the mean time between collisions with neutral atoms, we require ωτ > 1 for the gas to behave like a plasma rather than a neutral gas.

^highlight-p24x53y311

Plasmas behave sometimes like fluids, and sometimes like a collection of individual particles. The first step in learning how to deal with this schizophrenic personality is to understand how single particles behave in electric and magnetic fields.

^highlight-p32x53y304

Important points

Such a distribution generally comes about as the result of frequent collisions. However, this assumption was used only to take the average of v2 xr. Any other distribution with the same average would give us the same answer. The fluid theory, therefore, is not very sensitive to deviations from the Maxwellian distribution, but there are instances in which these deviations are important. Kinetic theory must then be used.

[!quote]+ Note (Page 101)

The waves are pressure waves propagating from one layer to the next by collisions among the air molecules.

[!quote]+ Note (Page 108)

Parallel and perpendicular will be used to denote the direction of k relative to the undisturbed magnetic field B0. Longitudinal and transverse refer to the direction of k relative to the oscillating electric field E1. If the oscillating magnetic field B1 is zero, the wave is electrostatic; otherwise, it is electromagnetic

[!quote]+ Note (Page 126)

This wave, with E1 ║ B0, is called the ordinary wave. The terminology “ordinary” and “extraordinary” is taken from crystal optics; however, the terms have been interchanged. In plasma physics, it makes more sense to let the “ordinary” wave be the one that is not affected by the magnetic field.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 127)

waves with E1 ⊥ B0 tend to be elliptically polarized instead of plane polarized. That is, as such a wave propagates into a plasma, it develops a component Ex along k, thus becoming partly longitudinal and partly transverse.

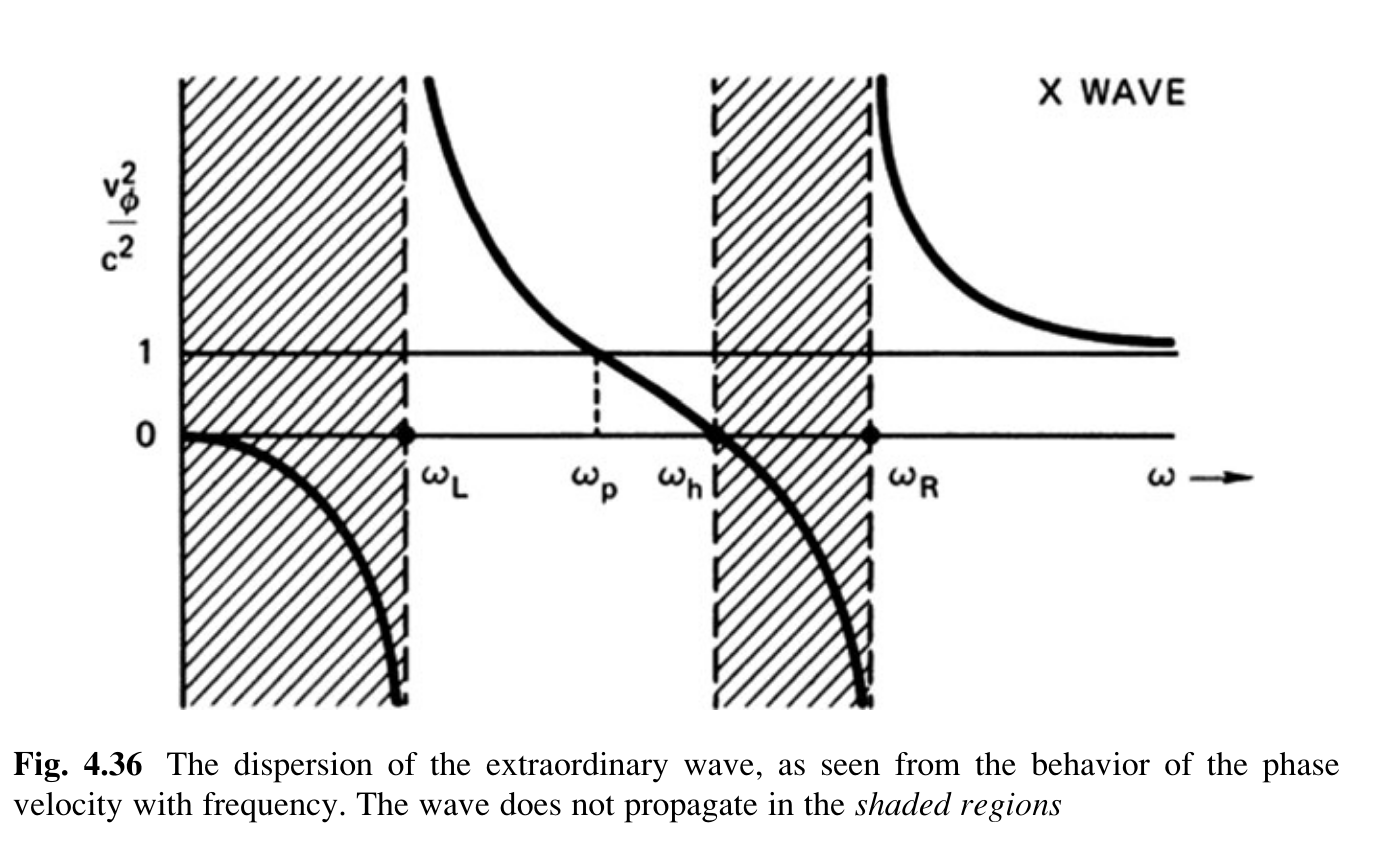

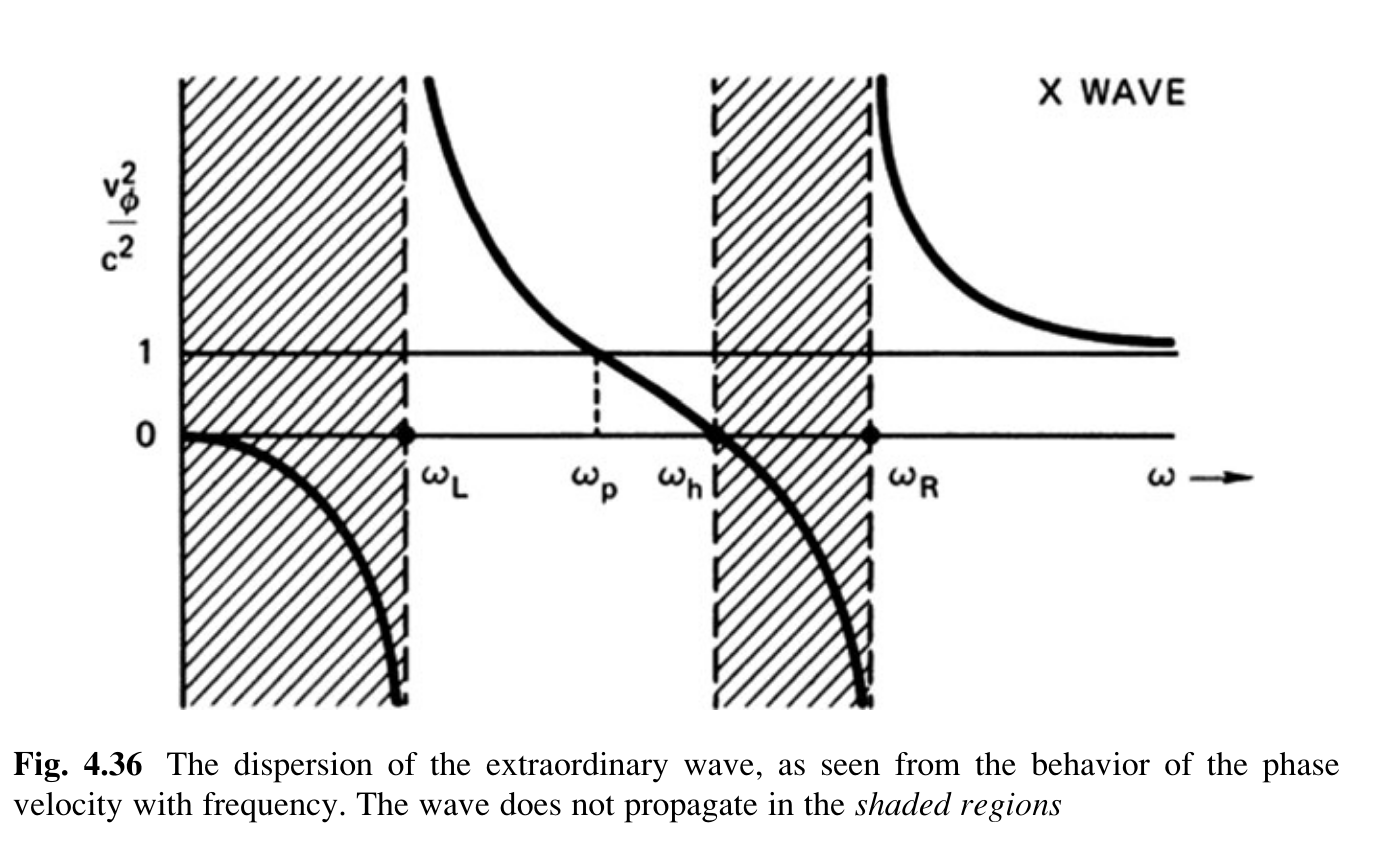

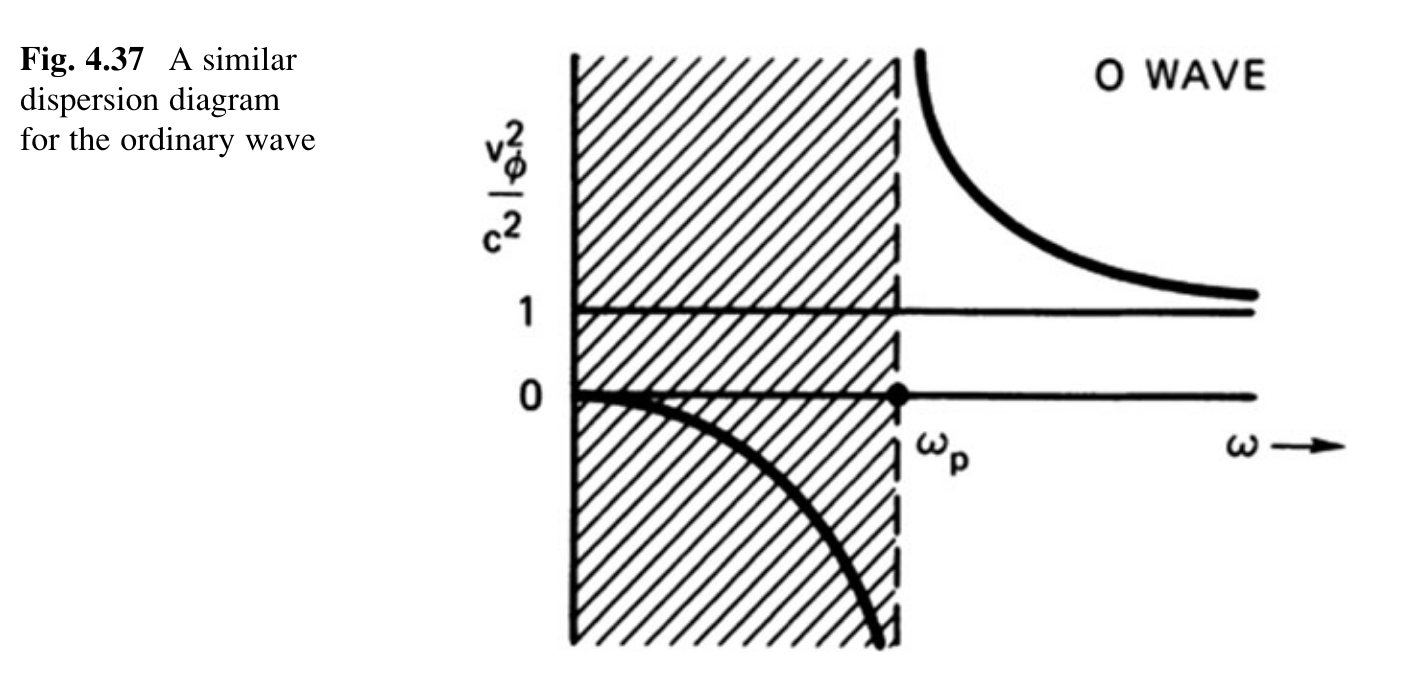

[!quote]+ Image (Page 131)

- Dispersion of extraordinary waves

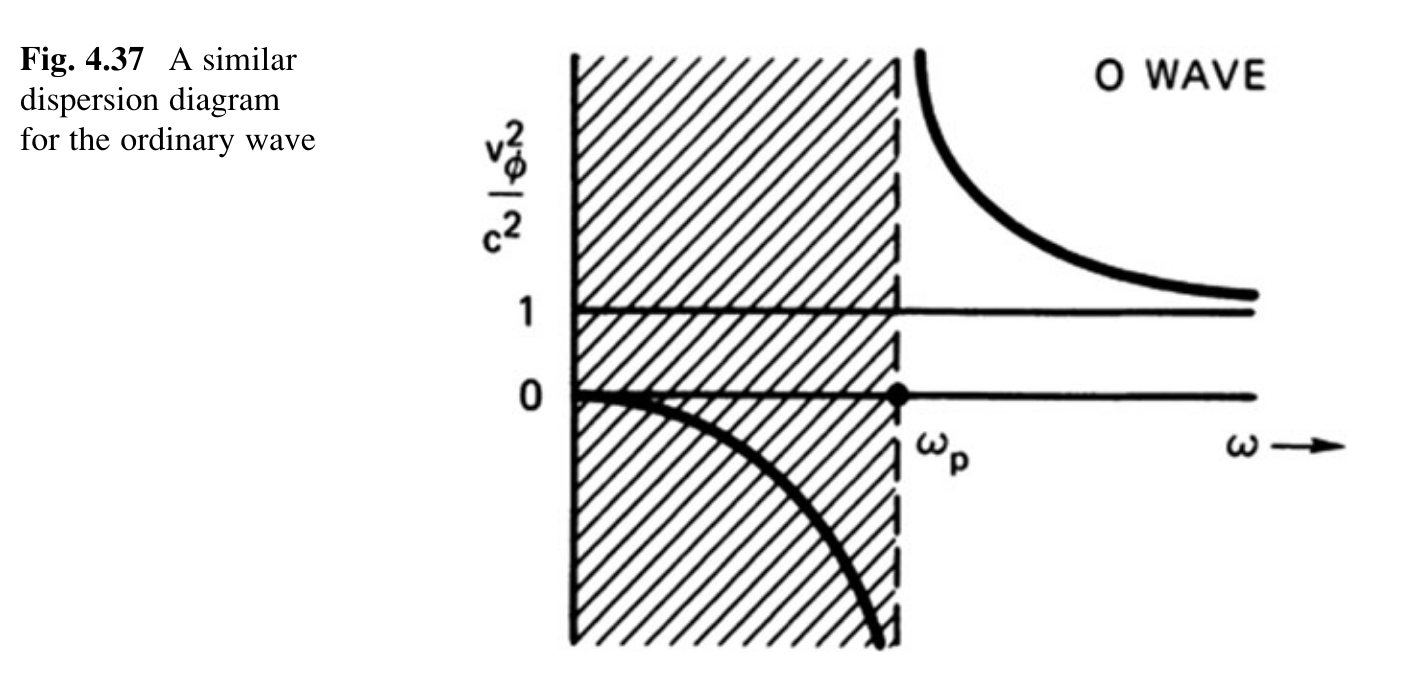

[!quote]+ Image (Page 131)

- Dispersion of ordinary waves

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 157)

As the plasma spreads out as a result of pressuregradient and electric field forces, the individual particles undergo a random walk, colliding frequently with the neutral atoms

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 184)

we have neglected the viscosity tensor π, as we did earlier. This neglect does not incur much error if the Larmor radius is much smaller than the scale length over which the various quantities change. We have also neglected the (v · ∇)v terms

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 229)

The Boltzmann equation (7.19) simply says that df/dtis zero unless there are collisions.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 229)

In a sufficiently hot plasma, collisions can be neglected. If, furthermore, the force F is entirely electromagnetic, Eq. (7.19) takes the special form ∂f∂tþ v ( ∇ f þ q mð Þ(Eþv ' B ∂f∂v ! 0ð7:23ÞThis is called the Vlasov equation

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 241)

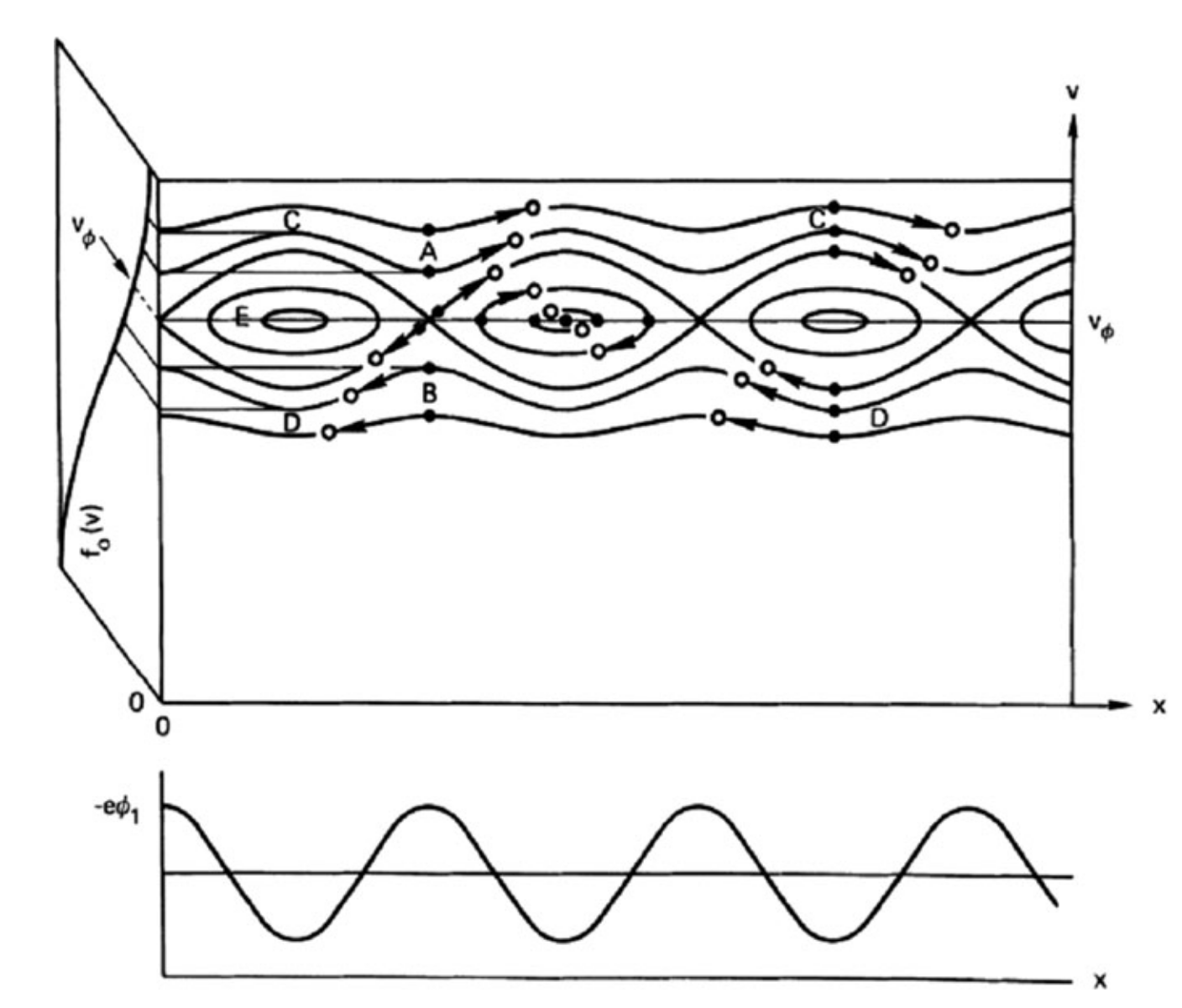

To see what is responsible for Landau damping, we first notice that Im(ω) arises from the pole at v ! vφ. Consequently, the effect is connected with those particles in the distribution that have a velocity nearly equal to the phase velocity—the “resonant particles.” These particles travel along with the wave and do not see a rapidly fluctuating electric field: They can, therefore, exchange energy with the wave effectively. #Take-aways

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 242)

A Maxwellian distribution, however, has more slow electrons than fast ones (Fig. 7.18). Consequently, there are more particles taking energy from the wave than vice versa, and the wave is damped. As particles with v vφ are trapped in the wave, f(v) is flattened near the phase velocity. This distortion is f1(v) which we calculated. As seen in Fig. 7.18, the perturbed distribution function contains the same number of particles but has gained total energy (at the expense of the wave). From this discussion, one can surmise that if f0(v) contained more fast particles than slow particles, a wave can be excited.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 243)

The neglect of (v1 · ∇)v1 in linear theory amounts to the same thing as using unperturbed orbits. In kinetic theory, the nonlinear term that is neglected is, from Eq. (7.45),...When particles are trapped, they reverse their direction of travel relative to the wave, so the distribution function f(v) is greatly disturbed near v ! ω/k. This means that ∂f1/∂v is comparable to ∂f0/∂v, and the term (7.73) is not negligible. Hence, trapping is not in the linear theory.

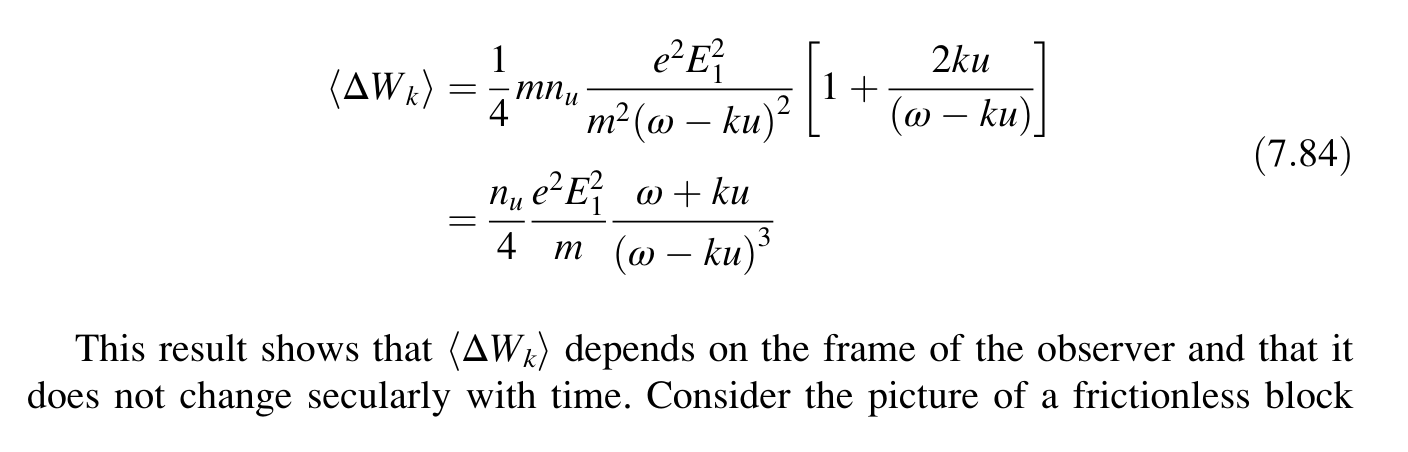

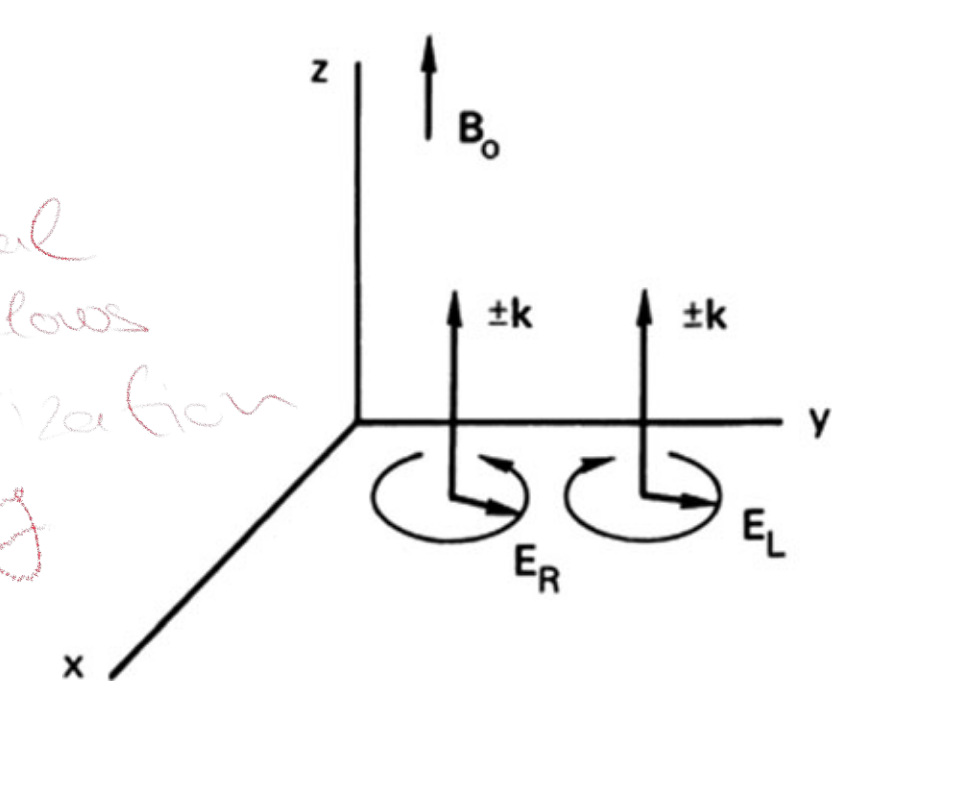

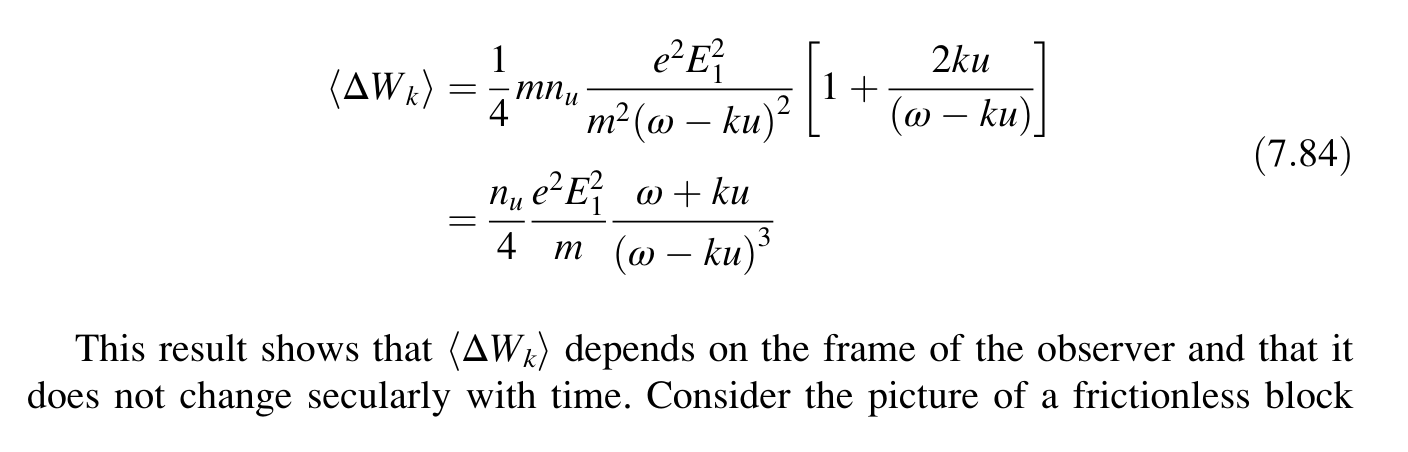

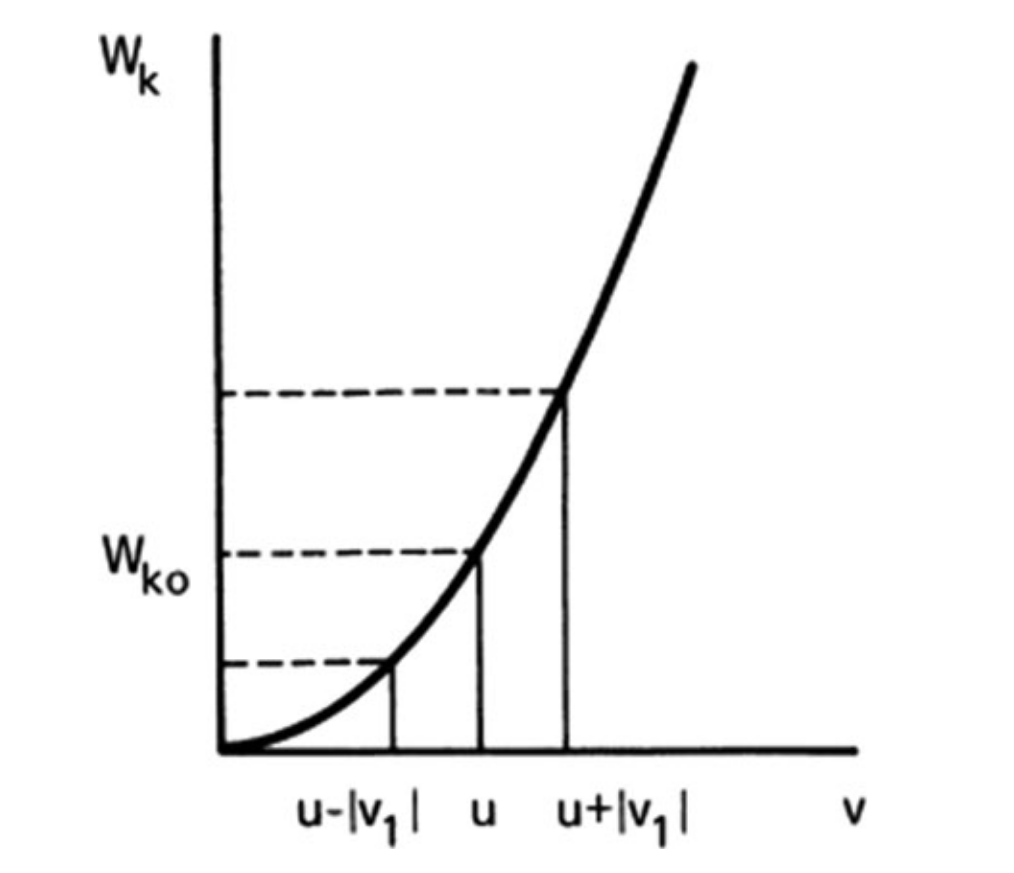

[!quote]+ Image (Page 246)

- Mean energy fluctuation of an electron beam traveling with a wave

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 247)

But Eq. (7.84) tells us that hΔWki depends on the velocityω/k, and hence on the frame of the observer. In particular, it shows that a beam has less energy in the presence of the wave than in its absence if ω $ ku < 0 or u > vϕ; and it has more energy if ω $ ku > 0 or u < vϕ. The reason for this can be traced back to the phase relation between n1 and v1. As Fig. 7.23 shows, Wk is a parabolicfunction of v. As v oscillates between u $ |v1| and u + |v1|, Wk will attain an averagevalue larger than the equilibrium value Wk0, provided that the particle spends anequal amount of time in each half of the oscillation. This effect is the meaning of thefirst term in Eq. (7.81), which is positive definite. The second term in that equation isa correction due to the fact that the particle does not distribute its time equally. InFig. 7.21, one sees that both electron a and electron b spend more time at the top of

[!quote]+ Image (Page 247)

the potential hill than at the bottom, but electron a reaches that point after a period of deceleration, so that v1 is negative there, while electron b reaches that point after a period of acceleration (to the right), so that v1 is positive there. This effect causeshΔWki to change sign at u ! vϕ.

- Parabolic relation of Kinetic Energy...

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 248)

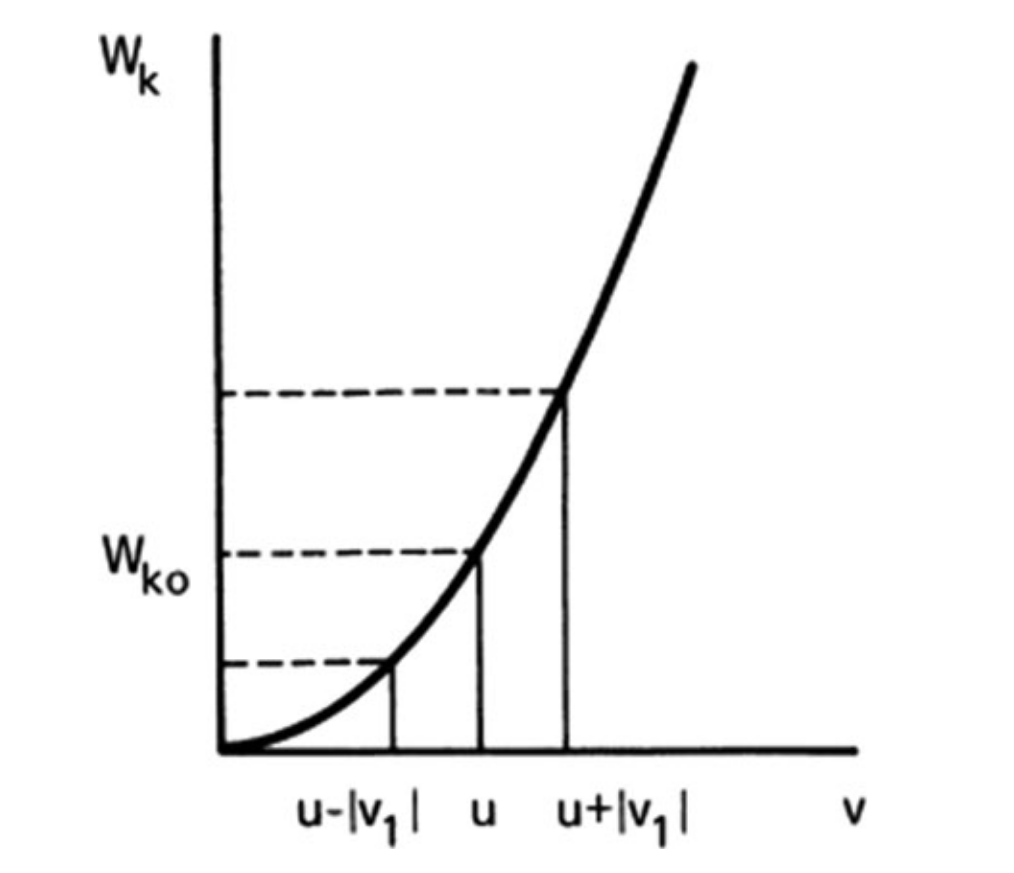

the electrons at A and D have gained energy, while those at B and C have lost energy. Now, if f0(v) was initially uniform in space, there were originally more electrons at A than at C, and more at D than at B. Therefore, there is a net gain of energy by the electrons, and hence a net loss of wave energy. This is linear Landau damping,

[!quote]+ Image (Page 249)

- Phase space for Landau damping

To understand the modes of plasma we need to understand the possible waves can propagate. In the Cold plasma model we can do this using the Dispersion relation.

Electrostatic

Longitudinal

Electron Plasma oscillations

Ion acoustic waves

++ Hybrid

Electromagnetic

Tangential waves

Electromagnetic waves perpendicular to B

Electromagnetic waves parallel to B

--> Whistler-mode waves

--> Alfven waves

--> Magnetosonic waves

Title: Introduction to Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion

Authors: Francis F. Chen

Zotero link: Francis Chen - Introduction to Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion-Springer 2015 Compressed 2.pdf

Green

A criterion for an ionized gas to be a plasma is that it be dense enough that λD is much smaller than L.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 23)

A criterion for an ionized gas to be a plasma is that it be dense enough that λD is much smaller than L.

^highlight-p23x53y241

Questions

Debye shielding can be foiled if electrons are so fast that they do not collide with one another enough to maintain a thermal distribution. We shall see later that electron collisions are infrequent if the electrons are very hot. In that case, some electrons, attracted by the positive charge of the ion, come in at an angle so fast that they orbit the ion like a satellite around a planet. How this works will be clear in the discussion of Langmuir probes in a later chapter. Some like to call this effect antishielding.

[!quote]+ Note (Page 75)

Langmuir discovered that the electron distribution function was far more nearly Maxwellian than could be accounted for by the collision rate. This phenomenon, called Langmuir’s paradox, has been attributed at times to high-frequency oscillations. There has been no satisfactory resolution of the paradox,

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 111)

Because of the symmetry of Eq. (4.60), the case ωc > ωp is the same as the case ωp > ωc with the subscripts interchanged. For large kz, the wave travels parallel to B0. One wave is the plasma oscillation at ω ! ωp; the other wave, at ω ! ωc, is a spurious root at kz ! 1. For small kz, we have the situation of k ⊥ B0 discussed in this section. The lower branch vanishes, while the upper branch approaches the hybrid oscillation at ω ! ωh. These curves were first calculated by Trivelpiece and Gould, who also verified them experimentally (Fig. 4.22). The Trivelpiece–Gould experiment was done in a cylindrical plasma column; it can be shown that varying kz in this case is equivalent to propagating plane waves at various angles to B0 #Question

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 117)

This is called the lower hybrid frequency. These oscillations can be observed only if θ is very close to π/2. #Question

- How do we excite these waves?

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 129)

As a wave of given ω approaches the resonance point, both its phase velocity and its group velocity approach zero, and the wave energy is converted into upper hybrid oscillations. The extraordinary wave is partly electromagnetic and partly electrostatic; it can easily be shown (Problem 4.14) that at resonance this wave loses its electromagnetic character and becomes an electrostatic oscillation.

[!quote]+ Image (Page 133)

- What is the physical mechanism that allows the R wave rotation?

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 134)

The L wave has a stop band at low frequencies; it behaves like the O wave except that the cutoff occurs at ωL instead of ωp. The R wave has a stop band between ωR and ωc, but there is a second band of propagation, with vφ < c, below ωc. #Question

- What is the physical cause of the cutoff?

[!quote]+ Image (Page 134)

- Understand whistler dispersion

[!quote]+ Note (Page 137)

In interstellar space, the path lengths are so long that Faraday rotation is important even at very low densities. This effect has been used to explain the polarization of microwave radiation generated by maser action in clouds of OH or H2O molecules during the formation of new stars. #Question

- How do we calculate the distance since we dont know the initial polarization? Can chaotic light get polarized and how?

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 146)

This is the dispersion relation for the magnetosonic wave propagating perpendicular to B0. It is an acoustic wave in which the compressions and rarefactions are produced not by motions along E, but by E * B drifts across E. In the limit B0 ! 0, vA ! 0, the magnetosonic wave turns into an ordinary ion acoustic wave. #Look-into

[!quote]+ Note (Page 170)

The steplength in the random walk is no longer λm, as in magnetic-field-free diffusion, but has instead the magnitude of the Larmor radius rL. #Question

- Where did we prove that the mean path is r_L?

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 242)

This is just the finite-temperature analogy of the two-stream instability. When there are two cold (KT ! 0) electron streams in motion, f0(v) consists of two δ-functions. This is clearly unstable because ∂f0/∂v is infinite; and, indeed, we found the instability from fluid theory. When the streams have finite temperature, kinetic theory tells us that the relative densities and temperatures of the two streams must be such as to have a region of positive ∂f0/ ∂v between them; more precisely, the total distribution function must have a minimum for instability. #Question

[!quote]+ Note (Page 243)

There are actually two kinds of Landau damping: linear Landau damping, and nonlinear Landau damping. Both kinds are independent of dissipative collisional mechanisms. #Question

- Since we derived it using linear theory, how can trapping not exist when there is energy transfer?

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 247)

84). It is intuitivelyclear that (1)hΔWkiis negative, since the block spends more time at the peaks than atthe valleys, and (2) the block does not gain or lose energy on the average, once theoscillation is started.

[!quote]+ Note (Page 248)

hiThese particles can absorbenergy from the wave and are properly called the “resonant” particles. As time goes on, the number of resonant electrons decreases, since an increasing number willhave shifted more than 1 2λ from their original positions. The damping rate, however,can stay constant, since the amplitude is now smaller, and it takes fewer electrons to maintain a constant damping rate. #Question

[!quote]+ Note (Page 249)

After a long time, the electrons are so smeared out in phase that the initial distribution is forgotten, and there is no further average energy gain, as we found in the previous section. In this picture, both the electrons with v > vφ and those with v < vφ when averaged over a wavelength, gain energy at the expense of the wave. #Question

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 23)

Debye shielding can be foiled if electrons are so fast that they do not collide with one another enough to maintain a thermal distribution. We shall see later that electron collisions are infrequent if the electrons are very hot. In that case, some electrons, attracted by the positive charge of the ion, come in at an angle so fast that they orbit the ion like a satellite around a planet. How this works will be clear in the discussion of Langmuir probes in a later chapter. Some like to call this effect antishielding.

^highlight-p23x53y62

Orange 🍊

Since T and Eav are so closely related, it is customary in plasma physics to give temperatures in units of energy.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 19)

It often happens that the ions and the electrons have separate Maxwellian distributions with different temperatures Ti and Te.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 19)

When there is a magnetic field B, even a single species, say ions, can have two temperatures. This is because the forces acting on an ion along B are different from those acting perpendicular to B (due to the Lorentz force). The components of velocity perpendicular to B and parallel to B may then belong to different Maxwellian distributions with temperatures T⊥ and T||.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 21)

On the other hand, if the temperature is finite, those particles that are at the edge of the cloud, where the electric field is weak, have enough thermal energy to escape from the electrostatic potential well. The “edge” of the cloud then occurs at the radius where the potential energy is approximately equal to the thermal energy KT of the particles, and the shielding is not complete. Potentials of the order of KT/e can leak into the plasma and cause finite electric fields to exist there.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 23)

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 23)

it is the electron temperature which is used in the definition of λD

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 23)

If the dimensions L of a system are much larger than λD, then whenever local concentrations of charge arise or external potentials are introduced into the system, these are shielded out in a distance short compared with L, leaving the bulk of the plasma free of large electric potentials or fields.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 23)

The plasma is “quasineutral”; that is, neutral enough so that one can take ni ’ ne ’ n, where n is a common density called the plasma density, but not so neutral that all the interesting electromagnetic forces vanish.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 24)

we can compute the number ND of particles in a “Debye sphere”:

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 24)

collective behavior

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 24)

If ω is the frequency of typical plasma oscillations and τ is the mean time between collisions with neutral atoms, we require ωτ > 1 for the gas to behave like a plasma rather than a neutral gas.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 32)

Plasmas behave sometimes like fluids, and sometimes like a collection of individual particles. The first step in learning how to deal with this schizophrenic personality is to understand how single particles behave in electric and magnetic fields.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 19)

Since T and Eav are so closely related, it is customary in plasma physics to give temperatures in units of energy. T

^highlight-p19x53y350

It often happens that the ions and the electrons have separate Maxwellian distributions with different temperatures Ti and Te.

^highlight-p19x53y184

When there is a magnetic field B, even a single species, say ions, can have two temperatures. This is because the forces acting on an ion along B are different from those acting perpendicular to B (due to the Lorentz force). The components of velocity perpendicular to B and parallel to B may then belong to different Maxwellian distributions with temperatures T⊥ and T||.

^highlight-p19x53y88

On the other hand, if the temperature is finite, those particles that are at the edge of the cloud, where the electric field is weak, have enough thermal energy to escape from the electrostatic potential well. The “edge” of the cloud then occurs at the radius where the potential energy is approximately equal to the thermal energy KT of the particles, and the shielding is not complete. Potentials of the order of KT/e can leak into the plasma and cause finite electric fields to exist there.

^highlight-p21x53y130

Note that as the density is increased, λD decreases, as one would expect, since each layer of plasma contains more electrons. Furthermore, λD increases with increasing KTe. Without thermal agitation, the charge cloud would collapse to an infinitely thin layer.

^highlight-p23x53y489

it is the electron temperature which is used in the definition of λD

^highlight-p23x53y476

If the dimensions L of a system are much larger than λD, then whenever local concentrations of charge arise or external potentials are introduced into the system, these are shielded out in a distance short compared with L, leaving the bulk of the plasma free of large electric potentials or fields.

^highlight-p23x53y325

The plasma is “quasineutral”; that is, neutral enough so that one can take ni ’ ne ’ n, where n is a ’ ’ common density called the plasma density, but not so neutral that all the interesting electromagnetic forces vanish.

^highlight-p23x53y265

we can compute the number ND of particles in a “Debye sphere”:

^highlight-p24x122y528

collective behavior”

^highlight-p24x150y480

If ω is the frequency of typical plasma oscillations and τ is the mean time between collisions with neutral atoms, we require ωτ > 1 for the gas to behave like a plasma rather than a neutral gas.

^highlight-p24x53y311

Plasmas behave sometimes like fluids, and sometimes like a collection of individual particles. The first step in learning how to deal with this schizophrenic personality is to understand how single particles behave in electric and magnetic fields.

^highlight-p32x53y304

Important points

Such a distribution generally comes about as the result of frequent collisions. However, this assumption was used only to take the average of v2 xr. Any other distribution with the same average would give us the same answer. The fluid theory, therefore, is not very sensitive to deviations from the Maxwellian distribution, but there are instances in which these deviations are important. Kinetic theory must then be used.

[!quote]+ Note (Page 101)

The waves are pressure waves propagating from one layer to the next by collisions among the air molecules.

[!quote]+ Note (Page 108)

Parallel and perpendicular will be used to denote the direction of k relative to the undisturbed magnetic field B0. Longitudinal and transverse refer to the direction of k relative to the oscillating electric field E1. If the oscillating magnetic field B1 is zero, the wave is electrostatic; otherwise, it is electromagnetic

[!quote]+ Note (Page 126)

This wave, with E1 ║ B0, is called the ordinary wave. The terminology “ordinary” and “extraordinary” is taken from crystal optics; however, the terms have been interchanged. In plasma physics, it makes more sense to let the “ordinary” wave be the one that is not affected by the magnetic field.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 127)

waves with E1 ⊥ B0 tend to be elliptically polarized instead of plane polarized. That is, as such a wave propagates into a plasma, it develops a component Ex along k, thus becoming partly longitudinal and partly transverse.

[!quote]+ Image (Page 131)

- Dispersion of extraordinary waves

[!quote]+ Image (Page 131)

- Dispersion of ordinary waves

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 157)

As the plasma spreads out as a result of pressuregradient and electric field forces, the individual particles undergo a random walk, colliding frequently with the neutral atoms

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 184)

we have neglected the viscosity tensor π, as we did earlier. This neglect does not incur much error if the Larmor radius is much smaller than the scale length over which the various quantities change. We have also neglected the (v · ∇)v terms

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 229)

The Boltzmann equation (7.19) simply says that df/dtis zero unless there are collisions.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 229)

In a sufficiently hot plasma, collisions can be neglected. If, furthermore, the force F is entirely electromagnetic, Eq. (7.19) takes the special form ∂f∂tþ v ( ∇ f þ q mð Þ(Eþv ' B ∂f∂v ! 0ð7:23ÞThis is called the Vlasov equation

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 241)

To see what is responsible for Landau damping, we first notice that Im(ω) arises from the pole at v ! vφ. Consequently, the effect is connected with those particles in the distribution that have a velocity nearly equal to the phase velocity—the “resonant particles.” These particles travel along with the wave and do not see a rapidly fluctuating electric field: They can, therefore, exchange energy with the wave effectively. #Take-aways

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 242)

A Maxwellian distribution, however, has more slow electrons than fast ones (Fig. 7.18). Consequently, there are more particles taking energy from the wave than vice versa, and the wave is damped. As particles with v vφ are trapped in the wave, f(v) is flattened near the phase velocity. This distortion is f1(v) which we calculated. As seen in Fig. 7.18, the perturbed distribution function contains the same number of particles but has gained total energy (at the expense of the wave). From this discussion, one can surmise that if f0(v) contained more fast particles than slow particles, a wave can be excited.

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 243)

The neglect of (v1 · ∇)v1 in linear theory amounts to the same thing as using unperturbed orbits. In kinetic theory, the nonlinear term that is neglected is, from Eq. (7.45),...When particles are trapped, they reverse their direction of travel relative to the wave, so the distribution function f(v) is greatly disturbed near v ! ω/k. This means that ∂f1/∂v is comparable to ∂f0/∂v, and the term (7.73) is not negligible. Hence, trapping is not in the linear theory.

[!quote]+ Image (Page 246)

- Mean energy fluctuation of an electron beam traveling with a wave

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 247)

But Eq. (7.84) tells us that hΔWki depends on the velocityω/k, and hence on the frame of the observer. In particular, it shows that a beam has less energy in the presence of the wave than in its absence if ω $ ku < 0 or u > vϕ; and it has more energy if ω $ ku > 0 or u < vϕ. The reason for this can be traced back to the phase relation between n1 and v1. As Fig. 7.23 shows, Wk is a parabolicfunction of v. As v oscillates between u $ |v1| and u + |v1|, Wk will attain an averagevalue larger than the equilibrium value Wk0, provided that the particle spends anequal amount of time in each half of the oscillation. This effect is the meaning of thefirst term in Eq. (7.81), which is positive definite. The second term in that equation isa correction due to the fact that the particle does not distribute its time equally. InFig. 7.21, one sees that both electron a and electron b spend more time at the top of

[!quote]+ Image (Page 247)

the potential hill than at the bottom, but electron a reaches that point after a period of deceleration, so that v1 is negative there, while electron b reaches that point after a period of acceleration (to the right), so that v1 is positive there. This effect causeshΔWki to change sign at u ! vϕ.

- Parabolic relation of Kinetic Energy...

[!quote]+ Highlight (Page 248)

the electrons at A and D have gained energy, while those at B and C have lost energy. Now, if f0(v) was initially uniform in space, there were originally more electrons at A than at C, and more at D than at B. Therefore, there is a net gain of energy by the electrons, and hence a net loss of wave energy. This is linear Landau damping,

[!quote]+ Image (Page 249)

- Phase space for Landau damping